In an optimal container supply chain, delays are minimised and container terminals are only a short-term link in the process. In practice, delays often occur here, most of which are due to other, external factors. One of the factors is the increasing size of container ships, which also increases the call size at a terminal. This increase in scale also impacts inland container shipping.

Increasingly large quantities of containers are loaded and unloaded at the same time and then have to be handled at and transported from the terminal. The ever larger container ships will also stay at the quay for longer periods of time, which reduces the space left for inland navigation vessels that have to transport the larger number of containers to and from the terminal. In recent years, inland waterway shippers have regularly complained about delays, waiting times and their poor position vis-à-vis the terminals. It would be going too far to discuss all the elements of this discussion here, but this article highlights one of them: the impact of the increase in scale of deep-sea vessels on inland container ships.

Container Ships Are Getting Bigger and Bigger

The scale of current container ships is still increasing; record ships are used on the east-west trade, with sizes increasing on other trade lanes as well. Shipping companies are looking for economies of scale, to reduce costs per container. This is because of the limited possibilities to differentiate the service as an alternative method to gain a competitive advantage; there is a need to compete at the lowest possible price.

The largest vessel at the time of writing this article is currently owned by the Chinese shipping company OOCL and has a capacity of 21,413 TEU. Hyundai Merchant Marine (HMM) has twelve vessels of 23,000 TEU in its order book [ed. the first of which was delivered in early July 2019] and Chinese shipping company Cosco is even considering using vessels with a capacity of 25,000 TEU.

According to Malchow (2017), the time has now come in which further increases in scale no longer bring any additional economies of scale for shipping companies. In addition, other chain parties such as terminal operators, ports and hinterland carriers are coming under increasing pressure to handle all containers. On the other hand, McKinsey (2018) outlines a scenario in which ships will grow to 30,000 TEU within ten years and in 2016 the same source predicted that 50,000 TEU ships would be in service by 2066. Therefore, it is uncertain what the maximum size will be, but for the time being, the current increase in scale seems to be continuing.

Impact of Increases in Scale on Deepsea Terminals

The larger vessels have a direct impact on the operations at deepsea container terminals. The increase in scale has resulted in larger callsizes – combined with the fact that the number of ports served on certain routes is sometimes reduced. Furthermore, more and more double calls – think of Rotterdam as a first and last port of call – are taking place at the terminals. As a result, ships spend more time in port and there is a greater peak load on the terminals because containers are only unloaded at the first of the double calls and only loaded at the second. Moreover, punctuality of deepsea container ships has definitely not increased in recent years; a low point was reached in 2018, with only 65 per cent of the ships arriving on schedule, especially at the beginning of the year (Murphy, 2018).

Large Deepsea Vessels and Congestion in Inland Navigation

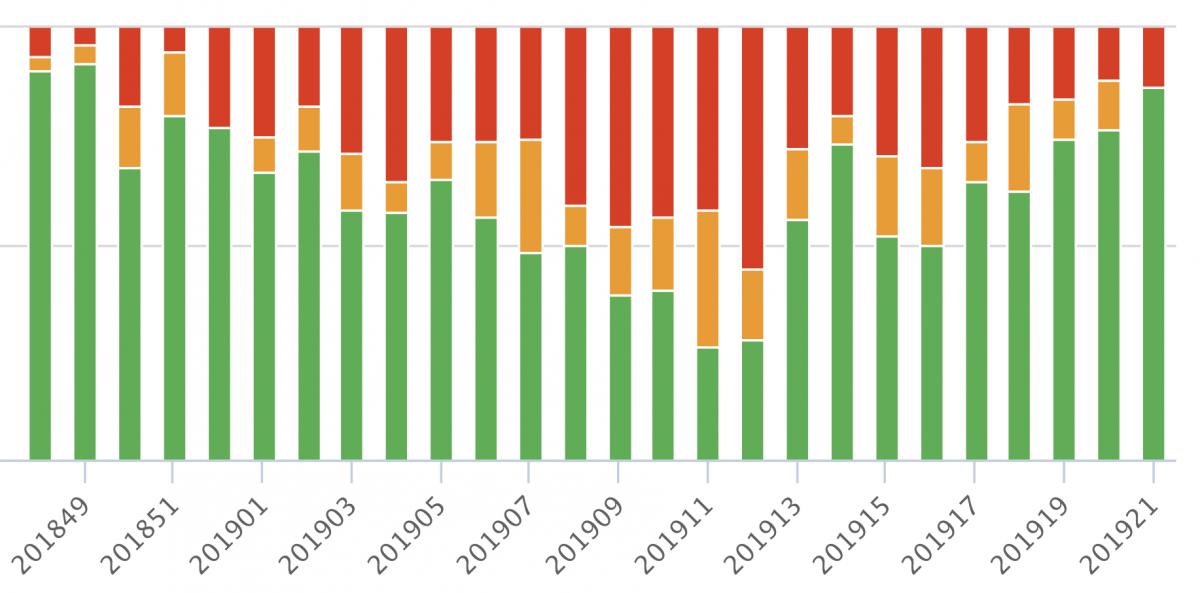

The consequences of ever larger container ships are not limited to the terminals, but directly translate into unreliability of hinterland connections, affecting mainly inland navigation. The Port of Rotterdam Authority maintains a "Barge Performance Monitor" in which the handling of inland shipping is monitored over time. As can be seen in the figure below, performance over the past few months can be described as very poor, with substantial delays that even occur in more than half of the cases in week twelve of 2019. In some cases, inland shippers have to wait a week before their containers are handled at the deepsea terminal (Evofenedex, 2017), but from their own observations at a large inland terminal in our country, it appeared that the delay this year amounted to one hundred hours: the system resets to zero after 24 hours of delay, meaning that the delay experienced by the hinterland connections is sometimes much higher.

The Barge Performance Monitor of the Port of Rotterdam Authority measures the handling of inland container ships in the port of Rotterdam. The week numbers are shown along the horizontal axis. Green means that the handling of a container barge went according to plan, orange indicates some delay and red indicates a large delay.

What is the relationship between terminals, ship owners and inland shipping and what role do economies of scale play in this? Five elements can be distinguished:

- Inland navigation vessels are often treated at the same quay as deepsea vessels. This ensures that a delay of a deepsea vessel, which increases as the callsize increases, immediately causes a delay in the handling of inland shipping. Some terminals – think of the terminals on Maasvlakte II in Rotterdam, the Netherlands – have a separate inland shipping quay (see photo below), but this is far from being the case everywhere.

- An inland waterway vessel must move away from the quay when a deepsea vessel arrives, even if the vessel is being handled at that time. This is due to the major impact of a deepsea vessel delay on the rest of the logistics chain.

- Deepsea terminals have no contractual relationship with inland navigation – in contrast to ship owners – which ensures that terminals have an incentive to primarily represent the interests of ship owners (Van der Horst and De Langen, 2008).

- The callsize of the deepsea vessels is increasing, as a result of which terminals have to handle more containers at the same time.

- The "Super Post-Panamax" container cranes are designed for the largest container ships. As a result, they are not suitable for handling inland shipping if no inland shipping quay is used. As a result, in some cases only a productivity of ten moves per hour can be achieved.

Adequate use of cranes specifically for inland navigation vessels is an important solution to congestion at deepsea terminals. Here, the RWG terminal on the Maasvlakte II in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Reverse Modal Split

The effects of congestion extend beyond deepsea terminals and inland navigation. Shippers are dissatisfied with the service provided and switch from inland shipping to truck transport. Congestion is one of the reasons for this so-called reverse modal split. Statistics from the Port of Rotterdam Authority show that this reverse modal split already started to take place in 2016: the share of truck transport increased from 53.3 to 54 per cent in 2016, while the share of inland shipping decreased from 36.2 to 35.6 per cent. In 2017, 58 per cent of containers and Ro-Ro were transported by road to the hinterland and only 30 per cent by inland shipping (Port of Rotterdam Authority, 2018). These figures are somewhat distorted by the presence of Ro-Ro, but it is clear that the desired modal split is not being achieved.

Failure to meet modal split targets and reverse modal split is detrimental both to terminal operators and to society. For the terminals because of the agreements made with the Port Authority about congestion and for society because transport by container by inland shipping is cleaner than by truck. In addition, public investments in inland shipping are not fully utilised as a result. Thirdly, shippers – and therefore consumers – will pay more per transported container. Finally, modern logistics concepts, such as synchromodal transport, will not take off (Van Riessen, 2018). Action is needed to counteract this trend.

Planning, Innovation, Trust and an Open Mind

A number of measures are being developed to reduce congestion in port. A first measure is the sharing of data relating to the planning of inland navigation vessels, which is crucial in order to make transport flows more efficient. Nextlogic is an example of a platform in which supply chain parties can exchange planning information with each other. Deepsea terminals, inland shippers and inland terminals share information here and the application ensures an integrated planning. The more parties are involved, the better the planning can be done.

In addition, it is possible to bundle containers between inland shipping terminal operators towards the deepsea terminals with the aim of increasing the call size and, thus, reducing the number of calls at deepsea terminals. This can take place both within one terminal operator (BCTN) and between competing operators (West Brabant Corridor). In addition, overflow hubs are being developed, such as in Alblasserdam, the Netherlands. This is where inland shipping terminal operators can drop their smaller callsizes. Several small callsizes are then bundled and transported to the deepsea terminals in a larger callsize. Interviews with inland shipping terminal operators in the Netherlands showed that they are all open to bundling, but that this is not always financially attractive due to the large distance between terminals in the hinterland and various infrastructural issues in which bridge heights are particularly crucial.

Another measure, which is often combined with the larger callsizes, is working with time slots – a specified time in which the handling takes place. Discussions have shown that this measure is experienced as very important by the various parties in the Rotterdam port network.

Work is also currently underway on the construction of the Container Exchange Route (CER) in the port of Rotterdam. The CER connects container companies on the Maasvlakte with the aim of facilitating the exchange of containers, so that inland shipping vessels no longer have to pass through all terminals and the number of calls is reduced. This CER should offer inland shipping a better competitive position compared to road and rail.

Ultimately, all parties in the chain – from ship owners to shippers – must work together to make the transport chain as free from delays as possible. Given the specific positions and perspectives of the various stakeholders, an optimal solution must be found that minimises congestion. Good management, innovative technologies, mutual trust and an open mindset are indispensable. A call on you to make this happen.

This article was originally published (in Dutch) as part of SWZ|Maritime’s June Port Special. Authors of the article are Port Economics Researchers Martijn Streng and Niels van Saase. Both are employed at the Erasmus Centre for Urban, Port and Transport Economics (UPT).

Picture (top): The OOCL Hong Kong measures 21.413 TEU, making it the largest ship to call on the port of Rotterdam to date.

References

- Evofenedex, acces date: 01/05/2019, www.evofenedex.nl/kennis/actualiteiten/overslag-containers-rotterdam

- Port of Rotterdam Authority (2018), Port of Rotterdam hinterland

- Port of Rotterdam Authority, access date: 01/05/2019, www.portofrotterdam.com/nl/zakendoen/logistiek/verbindingen/barge-performance-monitor

- Malchow, U. (2017), Growth in Containership Sizes to Be Stopped? Maritime Business Review, 2(3), 199–210

- McKinsey (2018), Brave New World? Container Transport in 2043

- Alan Murphy (2018), Containerliners Are Holding Their Breath, presentation Havendebat Rotterdam, 12 December 2018

- Van der Horst and De Langen (2008), Coordination in Hinterland Transport Chains: A Major Challenge for the Seaport Community, Journal of Maritime Economics & Logistics, 2008(10), 108-129