Ports and port cities are confronted with the substantial challenge of striking a balance between the pressure on space as a result of economic and urban development and pressure for sustainable development. Some port cities in the world – including Rotterdam – view this development as an opportunity and are explicitly profiling themselves as global maritime capitals.

These cities strive to develop into flourishing innovation ecosystems, but the art is how to orchestrate The art of it is to know how to orchestrate the ecosystem, how to combine thefinancial capital with the human capital of the port ecosystem and unlock shared value for businesses, communities and port citizens.

To the maritime sector, the port is a quay, a necessary transfer point for the shipper to move cargo between land and water. To the average person, however, a port comprises so much more. Currently, 55 per cent of the world population lives in cities, 37 per cent of which within 100 kilometres from the coast. According to the United Nations, 68 per cent of the world's population will live in cities by 2050, many of whom on the coast and in port cities.

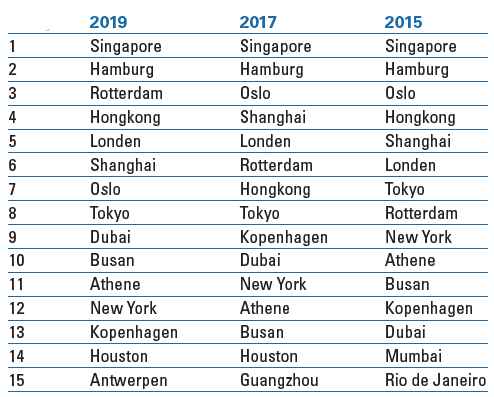

Rotterdam is keen to become a maritime capital – and, in view of Rotterdam’s higher ranking in the study that the Oslo-based consultancy firm Menon performs every two years (see table below), it is successful in this ambition. Rotterdam's strong point in Menon's latest benchmark is the port and logistics infrastructure, but the city is scoring higher across the board: as a shipping centre, in terms of maritime financing and legal services and particularly also as an attractive and competitive maritime hub.

Like other maritime hotspots such as Singapore, London, Hamburg, Shanghai, Oslo and Hong Kong, Rotterdam sees itself as a key driver of national and regional economies. However, a maritime capital does not spontaneously come into existence. The question as to where the innovative strength comes from and how this ecosystem can be enriched, in terms of both prosperity and well-being, is crucial for ultimately realising the ambition. The purpose of this article is to offer an impression of Rotterdam’s port innovation ecosystem and to deduce from that the factors that fuel that maritime knowledge development and innovative strength.

Dynamics in Rotterdam

It is precisely because ports are characterised by a dynamic international environment, with so many different stakeholders looking to safeguard their interests, that Rotterdam is so highly energetic. In recent years, the port innovation ecosystem has been enriched with various field labs, living labs, simulator centres and educational campuses and start-up incubator centres. In addition, educational institutions are increasingly strengthening their relationships; based on these partnerships, they are realising new concepts that develop into new knowledge platforms.

Maritime capitals ranked: 2015, 2017 and 2019 (source: Menon (2015, 2017, 2019)).

Room for Improvement in Connections Ecosystem

In a port that increasingly draws its competitive strength from the smarter, cleaner and more efficient production and organisation of logistics, data exchange and knowledge development are crucial. In various port cities around the world, it is apparent that the intensity of knowledge development and exchange is indeed increasing. It is quicker and easier to realise innovations if the connections in the port community are stronger, port city researchers Hall and Jacobs already concluded in 2012. Start-ups and incubator centres surrounding universities are welcomed by and in port cities, stated researcher Patrick Witte and his colleagues in 2018, but the quality of the connections between start-ups and other actors in the ecosystem – the business community and educational and research institutions – could be improved. According to these researchers, the extent to which start-ups have access to capital needs to be better facilitated as well.

| Sources of Maritime Capital | Description | Examples Rotterdam |

| Working capital | Possessions and assets of a company, both regarding capital goods and intellectual property (as valued on a company's balance sheet). | Vehicles, ships, cranes, real estate, patents and software. Consider the Pioneering Spirit. |

| Natural capital | Presence of natural resources, raw materials in the soil, biodiversity or animals (livestock). | Situation of port in a river delta, deep water, natural hinterland connections. |

| Human capital | Presence of individuals that are willing to invest in education in anticipation of higher returns in the future. | (Young) skilled labour force at all levels (STC, Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, Delft University of Technology, Erasmus University Rotterdam). |

| Cultural capital | A form of knowledge that is passed on from generation to generation through upbringing, socialisation and education. | Maritime DNA of the city, for example reflected in artefacts and masterpieces at the Maritime Museum Rotterdam and in cultural events. |

| Social capital | Networks in which people share common norms, values and relationships that facilitate cooperation within and between groups of people. | Port Association Rotterdam (including “Jong Havenvereniging” for young people), Marine Club Rotterdam, “Scheepvaartkring”, YoungShip Rotterdam. |

| Creative capital | A type of human capital that distinguishes itself through creativity, consisting of engineers, scientists, artists and performers, designers and architects, but also thought leaders and students who can bring about pioneering innovations. | PortXL, CIC, Studio Roosegaarde, World Port Hackathon, architects’ collectives at M4H. |

Sources of maritime capital (source: Jansen, 2019).

The Port as a Depository for Maritime Capital

Just as in nature, a thriving port ecosystem needs nourishment. The breeding ground for port cities consists of visible and invisible sources of capital: natural capital, human capital, working or industrial capital, cultural capital, social capital and creative capital, as per the previous table. The social capital of the city comprises the networks and the horizontal and vertical connections that are present within professional groups and associations and that, as such, act as lubricants between institutions. Port cities that are successful know how to effectively utilise this capital, and in such a way that social problems are minimised. Financial capital tends to generate better returns in an environment where forms of cooperation ensure capital deepening. Capital deepening occurs when the working capital is better utilised, for example by investing in human capabilities, which increases productivity.

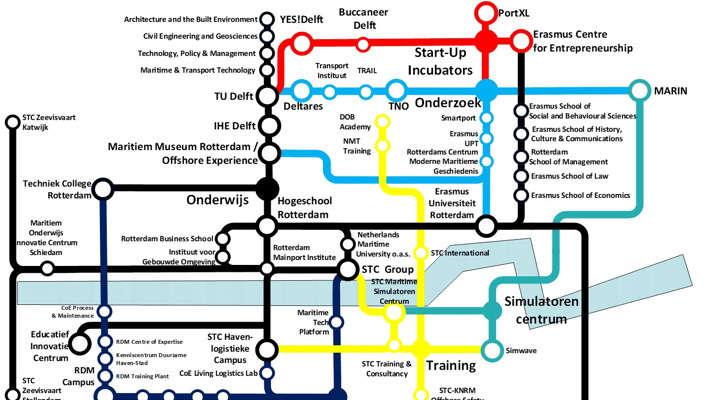

Metro Map of Maritime Institutions

It is possible to depict the relationship between port and city in the form of a “metro network”. The ecosystem of the port can be represented in different ways. In this article, the ecosystem is presented at two levels: the institutional level and the educational level.

A deliberate decision was made to only depict those institutions where knowledge-intensive activities related to education and research take place and where companies and educational institutions come together at innovation campuses, simulator centres and start-up incubators. In-house R&D centres and training facilities of companies have not been included on the map. The metro map is also a representation of the physical locations of education, research centres and innovation campuses. Unlike other conceptual models of port ecosystems, it is actually a snapshot of a dynamic ecosystem. In a well-functioning port ecosystem, new centres and connections emerge.

The main nodes are knowledge institutions such as Erasmus University Rotterdam, Delft University of Technology, STC and Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, but also research centres such as TNO (Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research) and Deltares. These nodes can boast a rich tradition and form the pillars on which the maritime capital has been built.

Also featured on the map are the Educational Information Center (EIC) and the Maritime Museum Rotterdam. The EIC is included because the centre – which recently marked its 25th anniversary – has played an important role in introducing the port to younger generations over the years. By doing so, the EIC has made countless young inhabitants of Rotterdam aware of the possibilities of a career in the port and maritime sector. The Maritime Museum is important because it provides a platform for storytelling of the maritime present and past to a wider audience who is often unfamiliar with, thus connecting generations with each other.

The metro map of institutions shows where companies and educational institutions come together.

What can also be deduced from the metro map is the amount of new “stations”, places where the business community, the education sector and entrepreneurs can come together to develop new innovations. The RDM Campus in particular is a good example of this, but the institutional cooperation between STC and Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences and the mutual cooperation between STC, Rotterdam College of Technology and Da Vinci in the Centres for Innovative Craftsmanship have also strengthened the port ecosystem by connecting training courses with one another and by allowing parties to make more optimum use of each other's locations and training facilities. Strong dynamics have also developed around TU Delft and Erasmus University Rotterdam. Yes!Delft has been in existence since 2005 and is on par with the best start-up incubator centres in the world (UBI Global, 2019).

Metro Map of Maritime Education

A second way to charter the maritime knowledge of Rotterdam is to connect training courses with one another. The courses illustrate where specific port knowledge is transferred and passed on to next generations. This too is a dynamic set of continuous learning trajectories that lead to a variety of professions in one of the seven subject courses on offer. The educational institutions on the training map have been made subordinate to the learning trajectories. We distinguish seven primary learning trajectories:

- deep sea shipping and inland shipping,

- sea fishery,

- logistics and supply chain management;

- shipbuilding and yacht building,

- hydraulic engineering, dredging and offshore,

- port logistics, and

- process engineering and maintenance.

In addition, there are secondary learning trajectories for the port. Technical service and maintenance are related to process engineering, while woodwork and carpentry are related to yacht building. For the sake of clarity, it has been decided not to include these related courses on the metro map. What can be deduced from this map is the breadth and depth of the range of courses on offer. Rotterdam has seven almost complete maritime and port-related learning trajectories, which comprise 58 educational courses in total, fourteen of which at the master's level, nine at the bachelor's level, one associate’s degree, 34 vocational courses and two pre-vocational courses.

The metro map of training courses shows where specific port knowledge is being transferred to the next generations.

A Symbiosis of Maritime Capital?

The development of the port innovation ecosystem has now been illustrated in two ways: on the one hand based on institutions and on the other hand based on educational options. The metro map is more than just informative and illustrative. The added value of this illustrative approach lies in the fact that it shows the coherence between knowledge-intensive activities within the ecosystem, both in a geographical sense and in a relational sense.

In scientific literature there a debate as to whether such an innovative ecosystem must necessarily develop in the vicinity of the port itself. By geographically positioning both the institutions and the education programmes, this can be refuted. In other words, the metro map of institutions does indeed reflect the locations where old port areas have transformed themselves and where knowledge-intensive educational and developmental activities are presently taking place.

The location of the RDM Campus on the shipyard of a former dry dock company is illustrative of this. There, entrepreneurs, researchers, students and teachers come together in the various field labs and networks. The “Lloydkwartier” area and the “Waalhaven Campus” have also been transformed and are now used by thousands of pupils and students. Finally, the Erasmus Centre for Entrepreneurship, which is located in the immediate vicinity of the M4H port area, shows that entrepreneurship is given space in this area where old and new, port and city, literally merge.

The connections between education, business sector and innovation campuses are maintained via knowledge workers: the students, teachers, researchers and entrepreneurs. In addition to Rotterdam, Schiedam and Dordrecht are also strengthening these links between education and business, as becomes evident from the map.

An ecosystem does not solely flourish due to its proximity to the port, but also because of the extent to which companies are able to draw on this ecosystem, namely the cultural, human and social capital of the city. Companies create value and in doing so make use of the capital that has accumulated in the maritime ecosystem: people, intangible assets, (corporate) cultures, standards for interaction, social networks, being able to easily approach one another, a great willingness to cooperate, and so on.

Cooperation cannot be taken for granted though. This needs to be managed and facilitated. Sometimes companies pro-actively do this, but usually it is the municipality or the port authority that connects knowledge and capital. Combined, this capital becomes more valuable than it would have been individually. The Offshore Experience in the Maritime Museum in the heart of the city is illustrative of bringing together the maritime capital of the city, but how the combination of these sources of maritime capital can lead to multiple value creation requires in-depth research.

| Learning Trajectory | Vmbo (Intermediate Preparatory Vocational Education) and Haven Havo (Secondary General Port Education) | Number of Vocational Education and Training Courses (level 2, 3 and 4) | Number of Bachelor's Degree Programmes (level 5) | Number of Master's Degree Programmes (level 6) |

| Logistics and SCM | 1 | 11 | 3 | 3 |

| Ocean shipping and inland shipping (nautical) | – | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| Sea fishery | – | 3 | – | – |

| Shipbuilding and yacht building | – | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Hydraulic engineering, dredging & offshore | – | 2 | – | 2 |

| Port logistics | – | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| Process industry & maintenance | – | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Vmbo and Port Havo | 2 | not applicable | not applicable | not applicable |

| Total number of courses (1) | 2 | 34 | 9 (3) | 14 |

| Total number of students (2) | 800 | 5750 | 2700 | 2000 |

Educational programmes per level and sub-segment. (1) This does not include the related training courses, such as the woodwork and carpentry college (5) and related technical training courses (17). (2) Due to considerable fluctuations in the data files of Dienst Uitvoering Onderwijs (DUO), the Education Executive Agency of the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, we have chosen to use the average number of registered students over the years 2015, 2016 and 2017. (3) Eight bachelor's programmes and one associate’s degree (level 5).

Transformation within Professions and Training Courses

The visualisation of the port innovation ecosystem also raises questions, such as how this ecosystem has been able to develop and especially the manner in which it has been able to adapt to the development of the port during the various stages of its evolution. On the other hand, the question arises as to what the knowledge landscape should ideally look like in ten or fifteen years. What new professions will appear when the port transforms itself into a digital platform and hub of the circular economy? Which technical training courses will have to be reinvented once energy is no longer largely generated from fossil fuels, but from renewable energy sources? The cross connections on the map also raise questions about the public-private partnerships that are present on the metro map, but that do not offer any insight into the degree of effectiveness.

Talent on Course

One thing is clear though: the port innovation ecosystem in Rotterdam is alive and kicking. This is attributable to its proximity to the port, but especially also to the many learning trajectories that steer the talent that is present towards future jobs in the port innovation ecosystem. That is an inexhaustible asset source for this maritime capital.

This article was previously published (in Dutch) in SWZ|Maritime's June 2019 Port Special and was written by Maurice Jansen MSc. Jansen is a senior researcher and business developer at the Erasmus Centre for Urban, Port and Transport Economics (UPT).

References

- UBI Global (2019), “The UBI World Benchmark Study 2017-2018 of University-linked Business Incubators & Accelerators”, Stockholm, Sweden

- Hall P.V., Jacobs W. (2012), “Why Are Maritime Ports (Still) Urban, and Why Should Policy-makers Care?”, Maritime Policy & Management, 39: 2, 189-206, DOI: 10.1080 / 03088839.2011.650721

- Jansen, M. (2018), "Mapping Port Ecosystem Talent", Port Strategy, London, UK

- Jansen, M., Van Tulder, RJM, & Afrianto, R. (2018), "Exploring the Conditions for Inclusive Port Development: The Case of Indonesia", Maritime Policy & Management, 45: 7, 924-943, DOI: 10.1080/03088839.2018.1472824

- Witte, P., B. Slack, M. Keesman, J.H. Jugie, and B. Wiegmans, 2018, “Facilitating Start-Ups in Port-City Innovation Ecosystems: A Case Study of Montreal and Rotterdam,” Journal of Transport Geography, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.03.006