The New Silk Road, formally known as the “Belt Road Initiative” (BRI), has caused quite a stir across the globe. Some mainly see opportunities in this mega investment programme of the Chinese government, others mostly threats. Of course, the question remains as to how the BRI will impact the competitive playing field between seaports in Europe.

The investments in ports in the Mediterranean, particularly in Piraeus and Valencia, and the more recent announcement of a partnership with Italian seaports are causing concern in the leading ports of north-west Europe. Are these concerns justified?

Many consider the BRI as an opportunity to attract investments, build infrastructure, improve connections and strengthen trade relations. For others, the BRI is a geopolitical challenge issued by China against the hegemony of the American-led West, a sophisticated strategy to acquire infrastructure assets by means of non-transparent financial constructions or, more specifically, a weakening of the current geographic positioning in relation to major trade routes. Chinese leader Xi Jinping recently addressed the growing degree of scepticism and criticism regarding the BRI, primarily from Western countries, during the “Belt and Road Forum” to emphasise that China’s intentions are sincere and that it does not pose a threat.

The Historic Silk Road

The historic Silk Road (see picture above) appeals to the imagination: caravans carrying precious merchandise such as silk, incense, porcelain and spices, connecting the Chinese empire through deserts and mountains via Central Asia with Persia, the Arabian peninsula and Byzantium. Access to this Silk Road allowed merchants from more distant European city states such as Venice, Genoa, but also Moscow, to amass great prosperity and wealth. Apart from the somewhat stereotypical image of camels traversing the desert in the time of Marco Polo, we in the West actually know very little about the tremendous importance and impact of this Silk Road on world history, says British historian Peter Frankopan.

For example, not many people are familiar with Chinese admiral Zengh He’s armada of trade ships in the fifteenth century, which made it all the way to Zanzibar in south-eastern Africa and to the Red Sea. Not only merchandise was exchanged through these routes, but also knowledge, money, technology, diseases, diplomacy and cultural customs: globalisation avant la lettre. A globalisation dominated by China, which would continuously remain the largest economy in the world for almost 2000 years until the mid-nineteenth century.

New Silk Road Dedicated to Connectivity

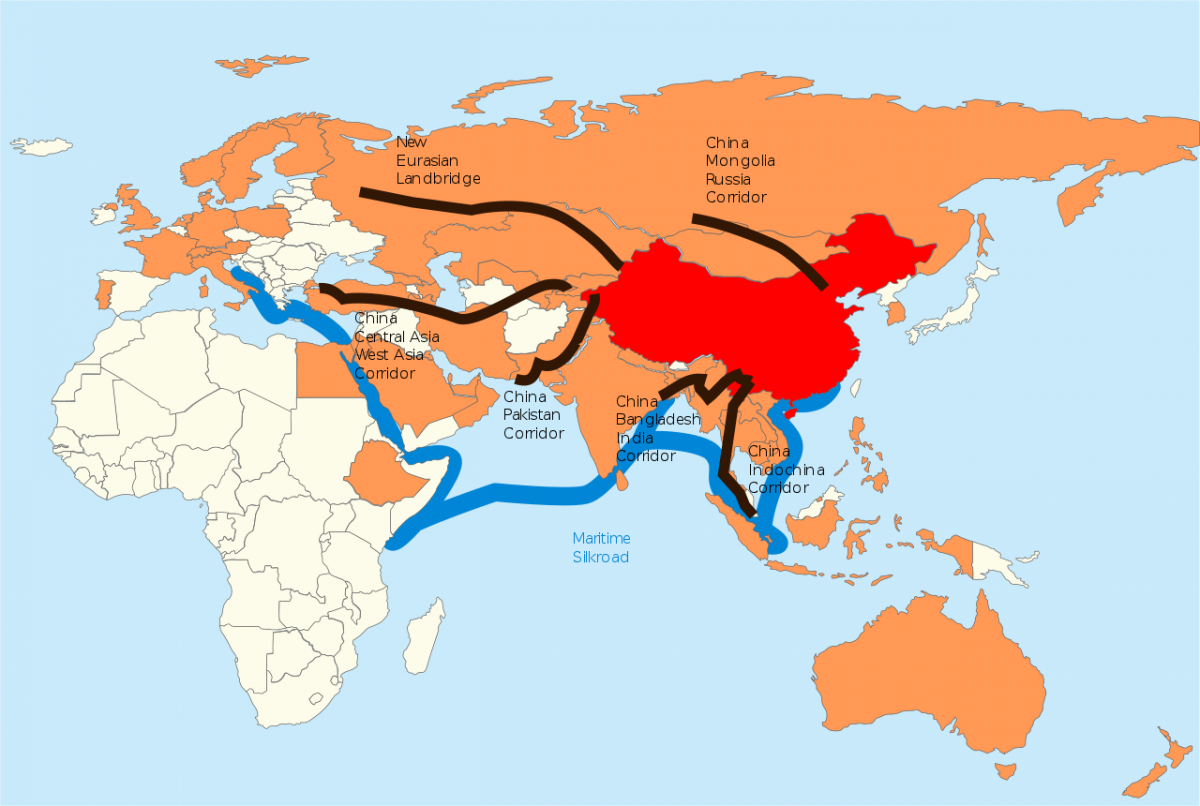

Fast forward to the present. In less than forty years, China has managed to successfully re-emerge as a global superpower. With the appointment of Xi as Secretary-General of the Communist Party in 2012, a new strong leader has emerged who has consolidated his power within the Communist Party and the Chinese State and at the same time has launched the ambitious “One Belt-One Road” programme, or the New Silk Road. The programme, later renamed the BRI, was quickly accompanied by geographic projections that clarify China's global ambitions. As was the case with the historic Silk Road, the key word is connectivity. This connectivity comprises five related dimensions.

- Infrastructural connectivity. The most concrete dimension and initially the main focus of media attention. The emphasis is on improving the logistics infrastructure (rail, road, shipping), initially with neighbouring countries in Central and Southeast Asia, which should primarily promote the economic development of western China (thus building on the “Xi bu dai Kaifa” programme of Xi’s predecessor, the economic stimulation of China’s western and central regions).

- Trade connectivity. Improved infrastructure allows for the promotion of trade, both upstream and downstream in the value chain. The Chinese economy continues to have a huge appetite for resources to fuel the industrial sector, enable cities to grow and keep the middle class satisfied. These resources need to be secured upstream; in Kazakhstan, Iran, the Middle East and Africa. Furthermore, there is a need to grow the market for Chinese products and manufacturing. It is particularly in the downstream countries of the Silk Road in Asia and Africa that many telephones, cars, household goods and business services can be sold and possibly manufactured at much more cost-effective prices than in China itself.

- Financial connectivity. China’s trade surplus with the global economy – there is a trade surplus with the West, while there is a trade deficit with the developing countries plus Australia – means the country has a lot of cash: US dollars. This money yields better returns when invested in infrastructure and real estate assets, not only in locations or sectors with a guaranteed return (for example real estate in London or Sydney), but especially also in locations and in sectors where demand (for Chinese products) can be stimulated in the long term and from which delivery of raw materials can be guaranteed. It is for this reason that China established the “Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank” in 2015 in order to allocate the surplus capital to investment projects in countries that need capital and that also want to commit politically to the BRI that has now been anchored in the Chinese constitution. After all, the same credit and loans could also be obtained from the American-dominated World Bank, under different conditions of course.

- Political connectivity. With international investment projects, diplomacy is activated and thus the political willpower for negotiating mandates and starting points. So, through the above-mentioned dimensions of the BRI, political cooperation, cross-linking and mutual dependencies are established. In a sense, this is what the Marshall Plan of the United States also endeavoured to do and has done. China is emphatically looking to strengthen and consolidate strategic political interests in international sales and supply markets: the BRI. This political connectivity is perpetuated through the striking number of state visits Xi pays to smaller countries in Europe, Asia and Africa. Just like the historic Silk Road, the BRI ultimately encompasses much more though. An explicit goal of the BRI programme is cultural exchange, a strengthening of the international awareness of China’s role in world history and in the future.

- Cultural connectivity: people-to-people. It is the Chinese scale, territorial scope, geographic positioning and history that gives the country an unprecedented, civilization-wide influence in “world affairs”. For years, the Chinese government has been promoting programmes aimed at “knowledge transfer through cultural exchange”, but this no longer exclusively takes place with the West. Chinese students have been dispatched to top Western universities for years, but now students from Africa and Central and Southeast Asia are actually being invited to China for educational purposes, all within the framework of a clear long-term vision.

China’s adoption of a more assertive and self-assured foreign policy plays a central role. This policy focuses on the ability of China to autonomously manage the vast domestic challenges in the country (Brown, 2018). The projection of influence associated with the BRI leads to reactions, in particular from America, which, after years of distraction in the Middle East and the War on Terror, is once again setting its sights on China as the primary geopolitical challenger.

China in red, the member states of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in orange, the six land corridors in black, the shipping route in blue (image: Lommes).

Positioning of European Seaports

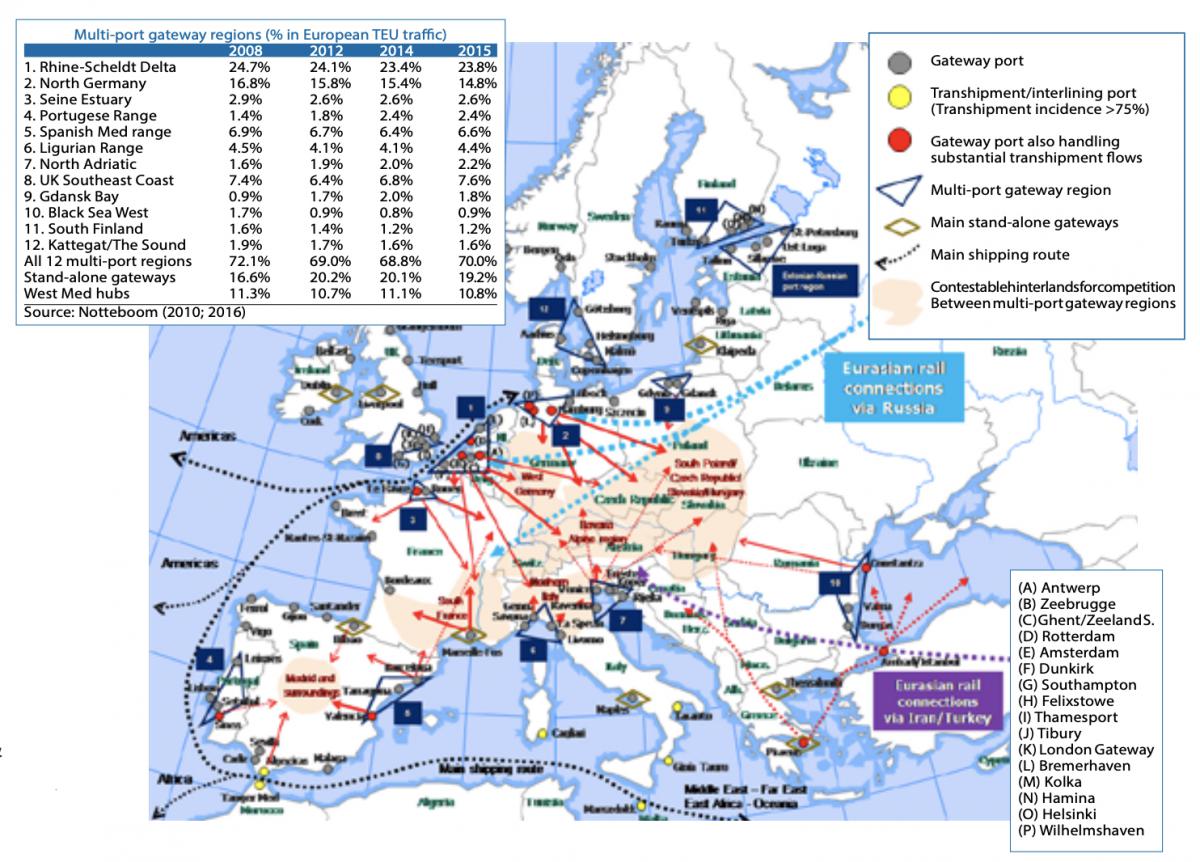

The studies of the Flemish professor Theo Notteboom, who frequently teaches in China, show the changing competitive playing field in Europe. Ports are grouped in ranges of multiport gateway regions that, due to geographic proximity, compete for cargo, calls and market share in an overlapping hinterland.

The ports in north-west Europe are often referred to as the Hamburg-Le Havre range, which also includes Rotterdam, North Sea Port and Amsterdam. This has traditionally been Europe’s leading gateway region, with the Rhine offering access to the vast economic hinterland. The depth of the ports combined with outstanding nautical services and existing investments in terminal infrastructure mean that these seaports still handle the lion's share of European container trades to and from Asia. This becomes apparent from the table that has been inserted in the figure below, which shows that the market share fluctuates around 24 percent.

Multi-port gateway regions in Europe, logistics centres and the BRI (source: Notteboom, 2017).

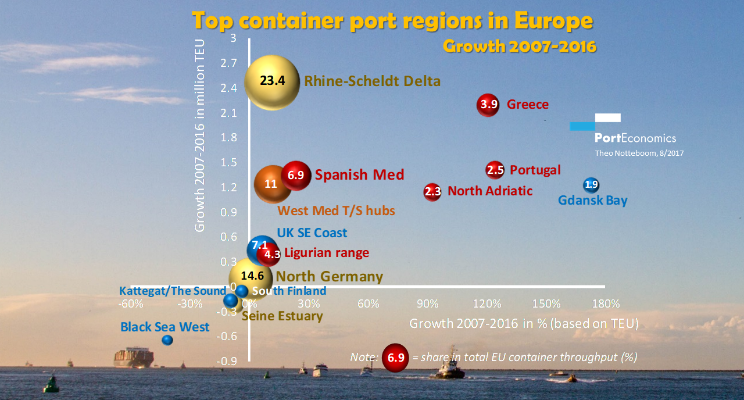

The ports around the Mediterranean may be situated more favourably in relation to the shipping routes to and from Asia, but they are often limited by the quality of infrastructure and logistics services, the scale of operations and the restricted hinterland connections. It is in these areas that the BRI can indeed have an impact, through improved infrastructure, better terminal management and guaranteed calls due to the fact that the main Chinese shipping line also controls the terminal infrastructure. Over the years, container throughput in the Mediterranean ports has been clearly growing, although it is too early yet to attribute this to the BRI. What does stand out in this respect though is the growth of Piraeus (also see the figure below).

The investments that are being made in rail as part of the BRI are substantial and not a month goes by without a new rail connection being announced between a location in Europe and a vast city in China. Despite this, the volumes are still limited though; there is serious doubts as to the continuity of some of these services and there are numerous operational and institutional bottlenecks that hamper growth. Given the relatively high costs in relation to maritime transport, the competitive power of rail remains limited. Moreover, the port of Piraeus still has very poor land connections to Central Europe and initiatives to develop this are complicated by institutional constraints in the fragmented Balkans.

However, other developments are in play that can contribute to a changing positioning of European seaports, such as the trend of near-shoring, mostly among Western multinationals. This means that much of the manufacturing and assembly that previously took place in China or elsewhere in Asia now takes place closer to home, especially in Central and Eastern Europe. Asian companies are increasingly opting for this region for final assembly and distribution as well.

One recent example is Liège, where the distribution centres of Alibaba are directly connected to China by rail. From a purely geographic point of view, ports in the eastern part of the Mediterranean, but also in the Baltic and Black Sea areas, are more favourably positioned in relation to the new logistics hotspots and distribution centres in Central and Eastern Europe than the ports in the Hamburg-Le Havre range. In view of this, a further development of rail transport may have a negative impact on the North Sea ports. It is therefore not surprising that the most recent announcement of further BRI cooperation between Italian seaports and China is cause for concern. It is striking how Xi, BRI investments in tow, is welcomed with open arms, mainly in countries in southern, central and eastern Europe; countries that incidentally face major budgetary problems and that highly welcome Chinese loans and investments. Previously, China already established the “16+1 dialogue” with independent countries; only after persistent insistence was the European Commission granted an observatory role.

The Geopolitical Agenda

There are also concerns about China’s true intentions regarding the BRI. Many see a geopolitical agenda behind the ambitions and investments. These suspicions are further fuelled by the fact that the Chinese financing arrangements and loans often lack transparency. For example, the port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka fell into Chinese hands after the Sri Lankan government was no longer able to meet its loan obligations. For India, China's investments in its neighbouring countries, including a terminal and naval base in Gwadar, Pakistan, arch enemy number one, are a thorn in its side. The investments are causing a strong sense of encirclement among Indians. China being awarded the lease concession of terminals in the Israeli port of Ashdod also set alarm bells ringing at the Pentagon and among Israeli security forces. A China policy is now being pursued in the Netherlands as well with a national government statement. Up till now, this discussion has revolved around national security in relation to the tender for the 5G network.

The changing attitude recently spurred the Chinese government to take out an official advertorial in the Dutch daily newspaper NRC Handelsblad: “Promoting the relationship between China and the Netherlands in the right way”. The fact remains that China is an important trading partner for the Netherlands and Europe. There are also Chinese investments in the port of Rotterdam and in other ports in the north-western European port region, such as in Zeebrugge and Antwerp. An underlying factor on the geopolitical agenda is that the Chinese want to gain access through the north and south sides of the “Blue Banana”, a metaphor for the European economic heart along the Rhine and an important region where the ports of north-western Europe are in competition with one another (also see the figure on the previous page).

However, the changing relationship between the United States and China, with the danger of Europe becoming divided between these two superpowers as it sees itself confronted with increasingly more difficult choices, is more important. The work of the influential geographer Mackinder (1904) is most illustrative in this respect. In his treatise “The Geographic Pivot of History” he focuses on the Heartland thesis. The Heartland is the Eurasian supercontinent. Mackinder states that those who control the Heartland ultimately control the global economy. Given the American and British interests at that time, this must be prevented, he states. An important geographic region where control of the Heartland is determined is Eastern Europe. Historically, the comparison with the BRI is – to say the least – remarkable.

Growth of container regions in 2007-2016: in millions of standard containers (vertical axis) and in percentages (horizontal axis, source: Notteboom, 2017, www.porteconomics.eu).

Shaping Minds

Competition between European seaports and seaport regions is of all times. It is normal for the conditions under which competition takes place to change. The eastward expansion of the EU and the emergence of China have already caused the global centre of economic gravity to shift to the East. Partly for this reason, a recent study by the Erasmus Centre for Urban Port and Transport Economics (Erasmus UPT) and Ecorys (De Jong, et al., 2019) already refers to the Gdansk-Le Havre range.

From a purely economic perspective, Chinese investments in terminal concessions and other infrastructure assets are welcome, as long as this takes place in a transparent manner. The problem is that said investments are made by state-owned companies, which consequently means there will always be ties to the Chinese government. This is not conform the rules of a market economy as applicable in Europe.

In addition, it is much more important from a strategic point of view to realise what the long-term strategy and purpose of these investments in Europe will be. Ultimately, it is not about the amount of TEU that may shift from Rotterdam to Piraeus, no matter how valuable this loss may be in the short term. What matters in the long term is control over strategic infrastructure and supply chains, the geographic projection of influence and the political support that comes with it. University professor of strategic planning Andreas Faludi stated it as follows: ‘Strategic planning is about shaping minds, not space.’ “Belt Road” or “America First”, the ambitions are clear: where does that leave Europe?

Picture (top): The historic Silk Road crossed Arabia, Somalia, Egypt, Persia, India, Java and China, among other territories.

This article was previously published (in Dutch) in SWZ|Maritime's June 2019 Port Special and was written by Dr W. Jacobs. Jacobs is a Senior Research Fellow at the Erasmus Centre for Urban Port and Transport Economics (UPT).

References

- Brown, K. (2018), “China’s World – What Does China Want?” London/New York: I.B. Tauris

- Frankopan, P. (2016), “The Silk Road – A New History of the World”, London/New York: Bloombury Publishing

- Jong, O. de, et al. (2019), “Onderzoek havensamenwerking – Bouwstenen voor een handelingskader”, Rotterdam: Ecorys/Erasmus UPT

- Mackinder, H.J. (1904), “The Geographic Pivot of History”, Geographic Journal 23 (4): 435

- Notteboom, T. (2017), “Belt and Road Initiative: de Rotterdam-Shanghai connectie – Naar een onderzoeksagenda”, presentation for the SmartPort/Cemil-workshop, 14 December 2017

- NRC Handelsblad (25-5-2019), “De relatie tussen China en Nederland langs de juiste weg bevorderen”, advertorial on behalf of the Chinese government by Xu Hong, Ambassador of the People’s Republic of China in the Netherlands