According to supply chain managers, only one thing matters: reliability. Competitive transport rates are important, but first and foremost customers need to know that the goods will arrive on time for production or sale. Digitisation plays a large role in making this process more transparent.

Besides the location of the goods, other relevant factors in this respect include the availability of capacity on certain routes and which transporter calls at a certain destination. Everything revolves around ensuring that goods arrive exactly on time and in a fully transparent manner.

Nowadays, it is mainly freight forwarders who happily make use of the track-and-trace solutions of transporters to track the cargo of their customers. The forwarder acts as an information broker, thus putting him in control. By definition, forwarders are asset-light and therefore more focused on the shipper, which gives them a substantial lead over transporters. Those relationships are rapidly shifting. Who or what are the forces that drive these developments? Which technology is leading in that respect and what about the adoption of said technology by chain parties in and around the port?

Technologies Are Coming Together

In terms of technology, a number of applications are starting to gain traction. To name a few: blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI), digital twin, Internet of Things (IoT), digital platforms and control towers and smart containers. They are coming together and are transforming the logistics chain into a digital environment. They also require an increasing degree of cooperation between the parties in the chain. In this digital world, more and more decisions in the chain are supported by real-time data and software to make that data transparent and accessible. This is aimed at minimising the transaction costs and maximising the reliability of the process.

The degree of disruption of a technology – the rapid process in which existing technology loses market share – depends on the speed with which this new technology is adopted by the market and the extent to which established parties are able to adequately respond to that. So what are the developments regarding digitisation for the port?

Blockchain

The expectations for blockchain were high a couple of years ago, but nowadays they are somewhat tempered. That does not mean that blockchain is not used though. One of the most discussed initiatives in the shipping industry is TradeLens by Maersk and IBM. More than a hundred parties, including shipping lines, logistics service providers, forwarders, ports, container terminal operators and shippers, have joined. The ambitions were clear: cost reduction in international transport, improved transparency and the elimination of paper documentation.

The biggest challenge does not appear to be the actual technology, but rather the establishment of an ‘ecosystem that is based on trust between competitors and the realisation of open standards that enable rival chain parties to use the same platform alongside each other’ (IBM/Maersk, 2018). Standardisation and interoperability seem to be the first priority. This also becomes evident from the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA) initiative launched by some of the largest shipping lines in the world, such as MSC, Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd and Ocean Network Express, in Amsterdam on April 10.

Digital Twin

In 2017, the digital twin was named as one of the ten most important technological trends by Gartner. The digital twin refers to a digital replica of physical objects and systems that can be used by IT specialists to perform simulations before the devices are used in practice. The ongoing development of AI, IoT and the possibilities for analysing large data files has created a need to simulate reality in a digital environment. Based on this, what-if scenarios are run that make it possible to predict how objects that communicate with each other will behave towards one another. Due to the increasing availability of IoT sensors, possibilities therefore arise to calculate efficiency savings, but, under given circumstances, also to make performance forecasts (Networkworld.com, January 31, 2019).

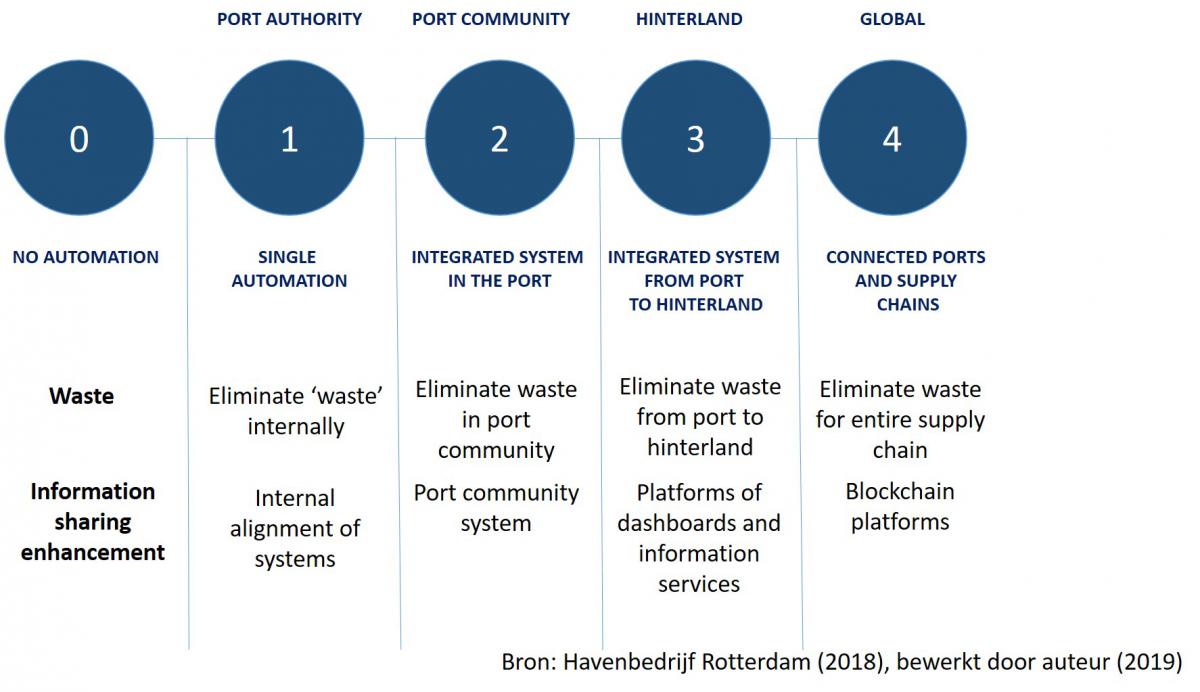

Digitisation of ports in four steps (source: Port of Rotterdam Authority, edited by author).

Digital Platforms and Control Towers

Digital platforms for booking cargo are increasingly gaining traction; for the average logistics service provider, the required investments in terms of research and development for establishing such a platform, however, seem too steep. A digital platform retrieves large amounts of data sets via programmed interface applications (APIs). The information that can be derived from this is immediately made available again to countless customers via dashboards, enabling them to improve their decision-making process, for example regarding the booking and planning of cargo.

Control towers are easier to implement for logistics service providers because the software is available in the market. They use control tower software to offer multinationals across the globe a uniform level of logistics service provision by means of strategically located control towers. Here too, chain transparency plays a major role in being able to optimise route planning or to better assess risks in the chain and anticipate them in a timely manner. According to a recent survey (EFT/JDA, 2019), about half of the logistics service providers are considering establishing a control tower.

Port authorities are well on their way towards assuming the role of a digital platform. Singapore has drawn up a digital blueprint of the port. “CP4.0” is a call to established companies, but particularly to start-ups, to realise the container port of the fourth industrial era. This revolves around real-time connectivity between all parties in the chain through intelligent infrastructure and full chain integration without paper documentation.

In Hamburg, Antwerp and Rotterdam, there is a strong focus on the building of platform technology as well. On the one hand, “SmartPort” in Hamburg focuses on coordinating the arrival and departure of mega container ships and the ensuing planning of pilots, towing services, boatmen and agents. On the other hand, it aims to build intelligent networks by making transport and traffic flows and infrastructure more intelligent in order to operate more efficiently and minimise environmental pressure.

Container 42 will be gathering data for two years (photo: Grant Pinkney, Kramer Group).

In Antwerp, “Nxt Port” appears to be mainly geared to the bringing together of data so that this can be used by the market to develop smart solutions. Rotterdam goes a few steps further with Digital Business Solutions, a whole new division. In four steps, the Port of Rotterdam Authority wants to connect the logistics chain, both on the deepsea side and in the hinterland. Various applications of the “Port Forward” portfolio have now reached the market. One example is “Navigate”, which offers insight into the entire network of hinterland connections, depots and terminals, thus making it possible to propose intermodal routes to shippers and forwarders. “Pronto” is targeted at shipping lines, ship managers, agents and terminals with the aim of improving the planning and execution of the arrival process of ships together with the service providers in the port. Furthermore, a pilot is underway which involves the real-time sharing of data about the position of the container with numerous parties in the chain and there are various digital solutions in the pipeline.

Smart Container

It is becoming increasingly clear that the container is less and less just a black box. Maersk has already been offering remote container management to its customers since 2016. CMA CGM and MSC have adopted the technology of Traxens, a sensor technology that offers real-time insight into the status of the container: its location, whether it is being loaded or unloaded, but also the temperature and humidity. This company recently announced that it would purchase no less than 50,000 smart containers. At Transport Logistic 2019 in Munich, the research platform Container 42 was launched, involving a sensor-equipped container, which will make a two-year journey around the world to generate data for applied research.

Artificial Intelligence in Transport and Logistics

Shippers, technology providers and logistics service providers alike are increasingly showing an interest in AI/machine learning (EFT/JDA (2019)). AI refers to a form of intelligence that is executed by machines that are capable of approximating, automating and simulating human thinking and decision-making processes. AI has a capacity for self-learning and creativity which makes it possible to use technology to solve problems and control processes without human intervention.

Machine learning refers to a system that is designed to absorb information (such as datasets, for example) and learn from it by evaluating, categorising and, based on these observations, generalising these observations into an impression, concept or conclusion. Most people know AI from autonomous vehicles, such as from Google, but it is mainly traditional car manufacturers, together with their suppliers, who are taking concrete steps to provide components with sensors, algorithms and big data for (predictive) maintenance.

Logistics still offers ample room for improvement regarding AI, concluded DHL and IBM in a white paper from 2018. The back-office process of transport planning still comprises many repetitive tasks, such as collecting, copying and checking data and itineraries. Those tasks can be taken over by AI, enabling the transport planner to focus on exceptions and the customer. DHL and IBM also see application possibilities in terms of customs formalities, for example for the faster detection of fraudulent patterns.

Countless applications are possible in terms of route planning, but the essence boils down to making predictable the supply and demand of cargo, transit times and route optimisation in densely populated cities and for hard-to-reach locations. The ability to anticipate future demand allows for the conception of applications in retail and distribution. By combining demand patterns with other data – meteorological and demographic data and social media – the location of stock and the allocation of transport capacity can be planned in advance.

It appears as if the sky is the limit in terms of technological advancement. There is broad consensus though that new technology is adopted at a much slower pace than that it is developed. This is partly due to the lack of know-how and training to maximise the potential of (new) technology. For many companies, finding the right technology for the right customer and next scaling it up to an entire segment of customers (EFT/JDA, 2019) involves a learning process. The cooperation between chain partners is also a factor of relevance in this respect. For most of these chain partners, chain transparency is the most important reason for cooperation, but this cooperation is difficult to achieve if it is not managed.

Digitisation and Chain Partners in the Port

Making optimal use of data and digitisation benefits the entire chain and can make it more transparent, predictable and reliable. This can only be achieved through a further integration of systems, processes and technologies. The biggest obstacle is still the lack of trust between parties in the chain, whether this relates to a blockchain solution, AI or between chain partners themselves. Larger interests are at play between shipping lines, logistics service providers and tech companies as to what remains of the cake if chain integration leads to the elimination of unnecessary tasks and links.

Container shipping lines are involved in a fierce battle for survival. Not only is the scaling-up of ships extremely capital intensive, but it has also resulted in a very strong focus (thirty per cent) on operational costs (Lloyd's List, 26 April 2019). With digitisation, that focus seems to be shifting to the customer and to being able to provide full transparency of the container in the chain. The standardisation initiative confirms just how serious this group of shipping lines is to achieve a breakthrough in their relationship with the shipper.

The role of the forwarder has been the subject of debate for some time already, but they are moving forward as well. A recent survey among freight forwarders in the Netherlands and Belgium has shown that 94 per cent of respondents have some form of digital strategy. When asked about the future of the forwarder, only fifteen per cent say that the traditional role of the forwarder is superfluous, while 46 per cent see a future in closer cooperation with start-ups and 24 per cent expect that the major forwarders will at some point incorporate a start-up by means of a merger or acquisition. In any case, “Flexport” serves as proof that the digital forwarder is on the rise.

Opinions differ on the role that a port authority should play. Hamburg, Rotterdam and Antwerp are much more proactive in connecting and establishing chain cooperation. On the one hand, they do this by actively introducing new logistics concepts in the market, such as a rail shuttle, an internal lane or a hinterland corridor. On the other hand, they are assuming the role of software developer, data broker and dashboard provider and no longer solely act as providers of a Port Community System. By connecting to digital developments in the playing field of international logistics, port companies are switching to a higher acceleration of chain integration. With that, the times of independence and impartiality seem to have become a thing of the past. This digital service provision by port authorities is not undisputed, given the potential conflicts of interest with other digital providers.

Keeping up with the Acceleration

The digital twin brother of the port is no longer a dream; it is happening right here and now. Work and employment will change rapidly. To lead the shift towards digitisation of the port, a tight and well-functioning port innovation ecosystem is needed to ensure that young people and professionals are able to keep up with the acceleration.

Picture (top): The Port of Rotterdam Authority's Pronto ensures better planning of the arrival process of ships (source Port of Rotterdam Authority).

This article was previously published (in Dutch) in SWZ|Maritime's June 2019 Port Special and was written by Maurice Jansen MSc. Jansen is a Senior Researcher and Business Developer at the Erasmus Centre for Urban, Port and Transport Economics (UPT).

References

- Awe, A.O., master thesis: “Redefinition of the Role of Freight Forwarders in the Digital Age: A Study of the Consequence Effect of Logistics Start-ups and Online Freight Markets” (2018), STC Netherlands Maritime University, Rotterdam

- DHL/IBM, white paper: “Artificial Intelligence in Logistics” (2018), Germany

- Eyefortransport/JDA Survey: “The Global Logistics Report 2019”

- IBM/Maersk, “TradeLens: How IBM and Maersk Are Sharing Blockchain to Build a Global Trade Platform”, 27 November 2018, written by Todd Scott

- “Digitalisation Survey Identifies Owners Enthusiasm for New Tech”, Lloyd’s List, 26 April 2019

- Shaw, K., Fruhlinger, J., “What Is a Digital Twin? [And How It’s Changing IoT, AI and More]”, 31 January 2019, NetworkWorld.com

- Gartner Consulting, “Gartner Survey Reveals Digital Twins Are Entering Mainstream Use”, 20 February 2019