The KNVTS has a proud tradition to connect its vision on the future with a view on the historic past of shipbuilding practice. Time for the chair of the KNVTS Ship of the Year Committee Rien de Meij to take a step back and reflect on the idea of “vision”. Here is the story of “The essential ship”.

After the Heroic age of the Homeric Iliad comes a dark period which Hesiod describes as the “Iron Age”. This period then flows over into the eight-century proto-Geometric period. Potters start to enrich the decoration of vases with forms of people, animals and – in the so-called Orientalising style – with lions, panthers, rosettes, palmettes and lotus flowers.

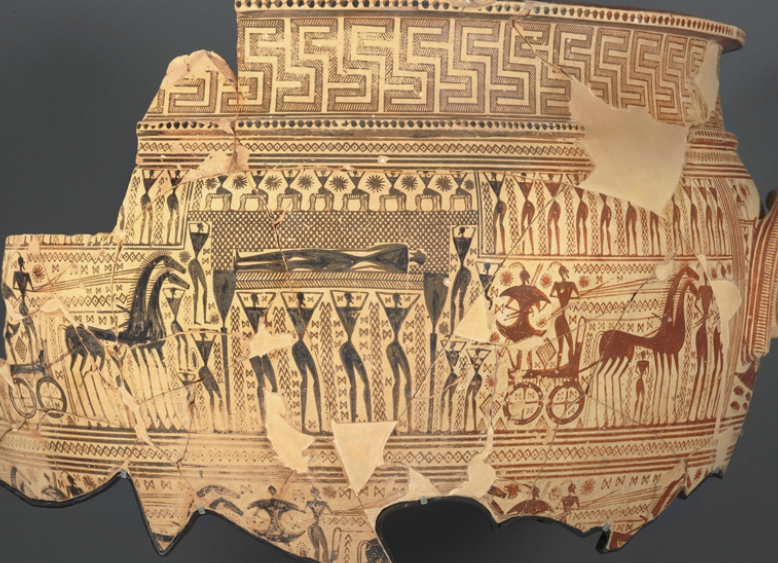

Lastly, in the Late Geometric period, the artists start to communicate with the viewer by adding narrative content to the decorations. The ships depicted on the vases of the Geometric period, however, are reduced to their essential lines. The artist decides on dimensions, aspect, and relative placement of the various elements on the basis of essence rather than in an attempt for realistic representation.

Around the mid-eighth century BCE the entrance of the Kerameikos cemetery in Athens is flanked by two pylons. Kratērs mark the places of males, amphorae those of females. They are painted in a Late Geometric style, many of them by the same artist; the so-called Dipylon Master (active 770 -750 BCE, Athens) (Denoyelle, M. 1994. Chefs-d’oeuvre de la céramique grecque dans les collections du Louvre).

Fragments of such a beautiful kratēr are shown in the figures. The vase, a grave-marker, is decorated with scenes of a funerary event; a corpse ’s procession, named ekphorae, showing the deceased on a bier flanked by mourners, passing silently through the streets of Athens (the vase is kept at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens). Everything suggests that the deceased was a naucraros: a member of the Athenian maritime nobility (Kirk, G.S. 1949, Ships on Geometric Vases).

Slender hull, curved keel and large stem

The section below the handles shows an elegant vessel with a slender hull, curved keel contour and a large stem with horned stem post. The representation of the ship is embedded in a compartmentalised system of metopes and triglyphs and surrounded by the decorative theme of the meander. Everything that matters is reduced to its essential ingredients and the decorative theme of the meander is the binding element (Moore, M. B. 2000, Ships on a Wine-Dark Sea in the Age of Homer).

Fore and aft of the bier are chariots, horses, and warriors carrying shields that are slender in the middle. Each human in the decoration consists of a triangle for a torso, the two long sides of which extend into arms which are raised in lament. The hands close above the heads, thus forming a second, larger, triangle. The faces point in the direction of the procession. The waistlines are slender; the legs are curved sections, providing a rather athletic profile.

The patterned veil, or shroud [speῖron] that has been put over the deceased is painted above him, rather than over him, so all parts can be depicted, and the dead man is shown as if viewed directly from above (the noun speῖron is used in the context of Pênelópê weaving the shroud; it appears in Homeric Odyssey 4.245 when Helene tells how Odysseus came in disguise to Troy wrapped in cloth. It is used for the sails of Phaeacian ships and for the sail on Odysseus’ raft when it is zapped by Zeus’ thunderbolt). For the same reason, the horses, standing beside each other, have their legs put in the same plane.

Dipylon vase: guardian birds surrounding the ship of the deceased.

Long-ship

The long-ship depicted below the handles of the vase is fitted with a raised half-deck [íkria], both at the stern [prumnos] and in the forebody [próra] (diērēs; derived from día = two, and eretmón = oar; a ship fitted with two ranks of oars on portside and two on starboard). The ship has a central walkway [thranos], connecting the fore- and aft deck.

The oarsmen of these open ships [áphraktos] were exposed to the sea and to enemies (the name áphraktos [undefended, not fenced] may be at the origin of our word “frigate”). They are depicted as if they are sitting on the central platform with their triangular bodies shown from the front. For the painter, their role within the depicted narrative is too essential to paint them sitting on benches, with only hands lifted above the side screens [parablemata].

It is not clear whether the ship is an Archaic fifty-oared long-ship [pentēkónteros], or a pre-Classic galley with oars operated on two levels [diērēs].

The ship is protected by long-necked water birds at the bow and stern and garlanded by the handles of the vase. The shape of the bird-heads — facing in the direction of the procession — regenerates in the curved contour of the stem post (the ship seems to be coming to meet the procession and take the body across the river Ōkeanós). This gives the impression of the ship being “straight-horned” [orthokrairáon].

The pointed cutwater [steira] is reduced to its essential lines and curves slightly upward in a continuation of the lines of the keel contour. The wheel in the side of the bow may be a decoration, or an enlarged eye [ophthalmós] to ward off the evil eye that may cause misfortune or injury, to the ship on its voyage to the Elysian Fields. The remaining spaces are filled with talismanic flowers and butterflies (the depicted butterflies may represent the psūkhē of the deceased: the essence of life while one is alive; conveyor of identity while one is dead).

We look at the athletic oarsmen framed in the section below the handles of the vase as if it were through a window. They keep the ship at speed. In the image, however, they are arrested in the stop-motion picture that tells the narrative of the depicted event.

Acknowledgements

Parts of this story have been published at the online community for Classical Studies of The Center for Hellenic Studies, Harvard University, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license (https://kosmossociety.chs.harvard.edu/?p=38944). Where possible, the images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses.

Figures: Maître du Dipylon, Cratère fragmentaire vers 750 avant J.-C. Musée du Louvre, Acquisition A 517. © 2009 RMN/Hervé Lewandowski.

Picture (top): Dipylon vase: transport of the mortal remains to the place of burial.

Series of articles

This is the fourth in a series of articles written by Rien de Meij. An abbreviated version of this article was published in SWZ|Maritime’s April 2020 issue. The other articles are:

This is the fourth in a series of articles written by Rien de Meij. An abbreviated version of this article was published in SWZ|Maritime’s April 2020 issue. The other articles are:

- “The theoretical ship” (also appeared in SWZ|Maritime’s January 2020 issue)

- “The modelled ship” (also appeared in abbreviated version in SWZ|Maritime’s February issue)

- Navigare necesse est: To sail is necessary (also appeared in SWZ|Maritime’s March issue)