The KNVTS has a proud tradition to connect its vision on the future with a view on the historic past of shipbuilding practice. Time for the chair of the KNVTS Ship of the Year Committee Rien de Meij to take a step back and reflect on the idea of “vision”. Here is the story of “The lost ship”.

‘Oceano Nox

Oh! combien de marins, combien de capitaines

Qui sont partis joyeux pour des courses lointaines,

Dans ce morne horizon se sont évanouis?

Combien ont disparu, dure et triste fortune?

Dans une mer sans fond, par une nuit sans lune,

Sous l’aveugle océan à jamais enfoui?’

(Victor Hugo 1840, Oceano Nox. Victor Hugo who wrote his novel upon the Greek word…Ananke.)

In the National Archaeological Museum of Athens there is a marble grave column with the relief sculpture of a young man in such regrettable condition (see picture above). The engraved text indicates that he is Demokleides, the son of Demetrios. The column (Athens, 380-370 BCE) once stood above an empty grave [kenotáphion] and the relief sculptured in the upper part of the column tells the story (“Kenotáphion” derives from kenos, meaning “empty”, and taphos, “tomb. In modern form it is often used as “cenotaph”; a saluting point for soldiers).

It shows a melancholic young man, wearing a short-girdled tunic, depicted in a pensive position; his right hand supporting his head, his left-hand rests on his lap. He is mourning himself; a lost “marine” [epibates] whose task it was to fight in hand-to-hand combat by boarding the decks of enemy ships in naval battles. The bow of the ship converges with the headland on which the person sits. His shield and helmet are positioned closely behind him. This marine had been lost at sea, and now we see him sitting at the board of his ship, overlooking the watery blue expanse that will not release his body for a proper burial in Mother Earth.

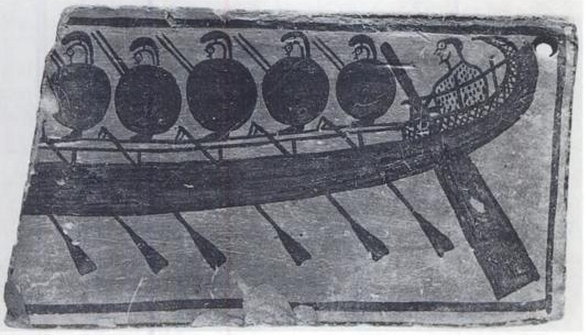

Sailors who had survived a terrible ordeal at sea or another unexpected event, or achieved some successful mission, would dedicate a votive to Poseidon or Amphitrite (“Hail, Poseidon, Holder of the Earth, dark-haired lord! O blessed one, be kindly in heart and help those who voyage in ships!” [Homeric Hymn 22 to Poseidon 6-7]). The thank-offering could be a small gift; like the votive tablet [pínax] represented below, which comes from Sounion. The fragment that remained of that plaque shows a fenced warship [katáphraktos] with marines [epibatai], oarsmen [erétai] and a helmsman [kubernētēs].

Votive plaque from Sounion, ca. 700 BCE (H. Phrontis. Plaque fragment. National Archaeological Museum of Athens No. 14935).

The warriors sit on a central platform [thranos], their faces directed towards the forebody of the ship. They keep their spears readily at hand. The faces of the oarsmen are hidden behind the side screens [parablemata] (side screens [pararrhymata, synonym parablemata]: Xenophon, Hellenica 1.6.19). Their hands are shown and from that we may assume that their faces look in the direction of the helmsman whose dress is depicted with a stippled pattern (the stippled pattern of the helmsman’s dress pattern may point at an Orientalized influence, comparable to the stippled patterns in the Proto-Attic work of the Anatolos painter (active 700-675 BCE)). There is a small hole in the right upper corner, possibly for fitting the votive tablet to the wall of a sanctuary.

When a sailor or traveler was saved from pirates or shipwreck, through the divine intercession of the Madonna or a saint, the wealthy would commission a painting depicting the capture or storm. The painting was then offered as a thanksgiving to the church which honored that saint (‘Chaíre olkás tón thelónton sothínai. Chaíre limín tón toú víou plotíron’: ‘Praise to you who are the safe ship for people that seek salvation. Praise to you who are the safe port for people who struggle swimming’ (in the sea of life) [Couplet from the Akathist hymn]).

These paintings were called “Ex-Voto” and both these paintings and the etchings on Malta have the same roots as the votive plaque of Sounion. Those who could not afford a painting, humbly etched the image of the ship involved into a rock or tree.

King Menelaos and Helen of Sparta

Another Homeric seaman who was lost in action, was King Menelaos of Sparta. He shipwrecked on the coast of Egypt where he unexpectedly runs into his wife, the beautiful Helen of Sparta. She had been kidnapped by Hermes – she never was in Troy; that was a cloud, an “empty tunic” [eídola]. In Egypt she stayed at the court of the Egyptian King Theoklymenes, ever mourning her presumably dead husband Menelaos. After they recognized each other they devised a way to escape from Egypt. Menelaos faked to be a messenger who reported himself, Menelaos, to be lost at sea.

Helen then tells her host, Theoklymenes, about the Greek funerary rites for lost and unburied seamen and asks permission for a ship to sail out and symbolically bury the absent body of Menelaos at sea, clothed in empty woven robes. Helen cleverly talks Theoklymenes into this, after which Helen and Menelaos escape in the faked funeral at sea; Menelaos himself now being the “empty tunic”.

A fascinating story about a seaman who was lost at sea, but refound himself as a rich man (“Helen” is a drama by Euripides, first produced in 412 BCE. ‘Helen is forever double. This ambivalence is, in fact, the essence of her tradition. She is the female forever abducted, but never finally captured’ [Bergren, A. 2008]).

Lastly, also Xenophon refers to the tradition of symbolically burying those whose bodies were lost in war, by erecting a cenotaph.

Acknowledgement

This story could only be formed thanks to the conversations in the CHS Kosmos Study Group of the online community for Classical Studies of The Center for Hellenic Studies, Harvard University, guided by Sarah Scott.

Picture (top): Grave column with sculpture of a young man. The Lost Ship (votive tablet from Sounion (c. 700 BCE). National Archaeological Museum of Athens, 380-370 BCE. Photograph by courtesy of Sarah Scott).

Series of articles

This is the sixth in a series of articles written by Rien de Meij. An abbreviated version of this article was published in SWZ|Maritime’s June 2020 issue. The other articles are:

This is the sixth in a series of articles written by Rien de Meij. An abbreviated version of this article was published in SWZ|Maritime’s June 2020 issue. The other articles are:

- “The theoretical ship” (also appeared in SWZ|Maritime’s January 2020 issue)

- “The modelled ship” (abbreviated version in SWZ|Maritime’s February issue)

- Navigare necesse est: To sail is necessary (abbreviated version in SWZ|Maritime’s March issue)

- The essential ship (abbreviated version in SWZ|Maritime’s April issue)

- The wine-dark sea (abbreviated version in SWZ|Maritime’s May issue)