A bulk carrier hitting a berthed tank barge after a helmsman confused port and starboard orders has resulted in USD 21 million in damages. The Nautical Institute discusses the incident in its latest Mars Report: ‘When in restricted waterways, the helmsman’s actions should always be verified by same-time sighting of the rudder angle indicator.’

The Nautical Institute gathers reports of maritime accidents and near-misses. It then publishes these so-called Mars Reports (anonymously) to prevent other accidents from happening. A summary of this incident:

A partially loaded bulk carrier was inbound in a port channel under pilotage. A rudder angle indicator was lit and, because the bridge had been darkened for night vision, it could easily be seen by the bridge team. The pilot conned the vessel from the centre line windows, the helmsman was directly behind him and the officer of the watch (OOW) was near the engine order telegraph just to the helmsman’s left.

Upon reaching a planned course alteration point the pilot gave a port twenty-degree command to start the turn. The helmsman answered, ‘Port twenty,’ but instead put the helm twenty degrees to starboard. About eleven seconds later, the pilot saw that the wrong helm direction had been applied so he ordered ‘midships’ then repeated the port-twenty order. Combined with a full-ahead burst of speed the vessel’s swing to starboard was arrested about 38 seconds after the original command to port had been given and the vessel regained the required heading.

Following the helmsman’s error and recovery, the pilot and OOW had a brief conversation about the mate’s duty to watch the helmsman.

The second mate agreed to double-check the helmsman with each command. The master was not on the bridge at the time. The OOW offered to call him, but the pilot declined. Although the OOW did not understand conversational English, he told investigators he understood the pilot’s orders.

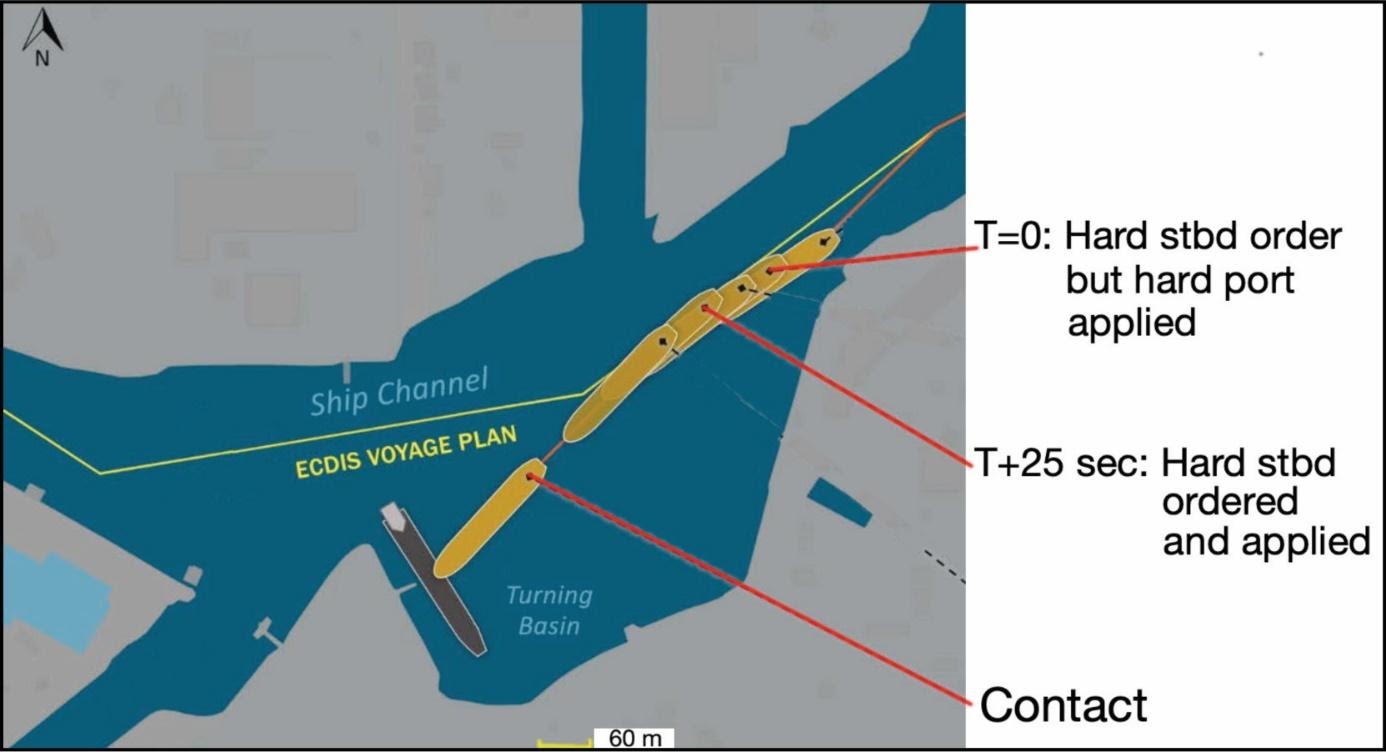

Some ninety minutes later, the vessel approached a major turn to starboard. By now the master was on the bridge. The pilot planned to turn wide, intending to stay to the south side of the channel to pass a working dredger. The pilot gave a port twenty-degree command to bring the ship slightly left, ahead of the turn to starboard, and the helmsman answered accordingly. The pilot’s next order to make the turn to the right, 24 seconds later, was ‘hard starboard’. The helmsman repeated the pilot’s order, but instead put the rudder hard to port.

Also read: Tanker hits buoy after bridge team loses situational awareness

Emergency manoeuvre needed

Ten seconds later, the pilot recognised the error and ordered midships while tapping with his fingers on the rudder angle indicator above his head to get the helmsman’s attention. It took the steering gear fifteen seconds to shift from hard port to midships, and then the pilot repeated his original hard-starboard order. The rudder reached hard starboard twelve seconds later, although the ship’s heading was still falling to port at about twelve degrees per minute. The pilot now realised an emergency manoeuvre was needed.

The pilot ordered ‘Stop engines; let go anchor’ and seven seconds later, ‘full astern’. The vessel’s whistle was sounded. At this point, the vessel was making about six knots and its heading was still falling to port.

The pilot estimated that increasing the engine speed to power through the turn, as he had done earlier, would not work so he chose instead to attempt to stop the vessel.

With the port anchor and two shots of chain deployed, the vessel nonetheless collided with the port side of a berthed tank barge while making almost four knots.

Fatigued and USD 21 million in damages

Although there were no fatalities or injuries as a result of this accident, the two vessels and the shore facility suffered damage that amounted to more than USD 21 million in total.

The investigation found, among other things, that the helmsman had probably been fatigued by carrying out extra duties the day before and that this contributed to the accident.

Also read: Ship hits mooring dolphins resulting in millions worth of damage

Advice from The Nautical Institute

- When in restricted waterways, the helmsman’s actions should always be verified by same-time sighting of the rudder angle indicator. A wrong rudder application may be irrecoverable if left for even ten seconds.

- The OOW was apparently not sighting the indicator at all and, if he was, he did not indicate the wrong rudder application to the pilot. The pilot was sighting the rudder indicator, but only after a ten- or eleven-second delay. In the first instance, they were able to recover, but not in the second.

- The work-rest log did not indicate the helmsman’s extra duties the day before. When collecting data for fatigue, investigators should not restrict themselves to looking at the work-rest logbooks, but should also question each person in detail about their previous 72-hour, or preferably 96-hour, work-rest routine.

Mars Reports

This accident was covered in the Mars Reports, originally published as Mars 202107, that are part of Report Number 339. A selection of this Report has also been published in SWZ|Maritime’s February 2021 issue. The Nautical Institute compiles these reports to help prevent maritime accidents. That is why they are also published on SWZ|Maritime’s website.

More reports are needed to keep the scheme interesting and informative. All reports are read only by the Mars coordinator and are treated in the strictest confidence. To submit a report, please use the Mars report form.